Acknowledging the complexity of contemporary educational leadership, the Australian Principal Standard recognises the crucial role of the principal in the 21st century as ‘one of the most exciting and significant roles undertaken by any person in our society’ (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, 2011, p. 2).

In part, this is because principals and teachers help to shape young people’s lives and deal with the hopes and dreams of their families. These responsibilities require leaders with strong emotional intelligence, an extensive range of technical information, professional skills and specialised knowledge. Further, the strategic and operational work ‘challenges school leaders and emerging principals to question, to be innovative, and especially to be self-aware and reflective’ (Hargreaves & Shirley, 2009).

Quality leadership is widely recognised as one of the most important drivers of improved performance, whether at the individual, team, school or organisational level. Coaching as a strategy, can help principals clarify their challenges, set clear directions and achieve sustainable improvements. ‘Coaching that has a focus on setting goals, collaborative problem solving practice, and using feedback to reflect on practice, can impact on a principal’s performance by as much as 88% compared to “one –off” types of professional development which is only 22%’ (Olivero, Bane and Kopelman 1997).

The Arnhem Empowering Learning Leaders Journey commenced in 2017, as part of an alignment of strategic priorities of the system, the region, and schools. It aimed to develop the capacity of Arnhem school principals and the regional Teaching and Learning managers who support staff in schools.

Significant challenges arise from the diversity, size and degrees of isolation that characterise Arnhem schools and communities, making the principal’s job particularly tough especially if they are new to whole school leadership. Productive professional relationships and timely support can make all the difference in development and wellbeing. Given the geographical range and diversity of the region, one of the hoped-for outcomes of this project was that principals would have someone other than the Regional Director and/or Assistant Director to call upon. The Learning Leaders Project offers a new model and approach to support principals in their work of school improvement and to address their specific professional learning needs.

Why was this model considered the best fit?

Like other schools and regions of the Northern Territory, the collective of Arnhem schools leaders have a range of experiences, skills and abilities. The current profile includes emerging principals, with some being new to remote Indigenous locations, having recently arrived from urban areas in the NT or interstate. The remaining profile consists of very experienced principals, some of whom have been in the region for a long time. Given the complexity and the ‘high stakes’ of education for students in remote communities, it was important that participants of the Empowering Learning Leaders Project had access to qualified coaches, who had previously been effective school leaders and who could tailor the coaching to each principal’s needs and context. This indicated that a more nuanced coaching experience than might otherwise be available was desired. The model of ‘professional companioning’ was seen by the Regional Director as potentially a ‘very good fit’ and a valuable resource, in addition to other structures already in place to support principals and school-based staff.

What is professional companioning?

Leoni Degenhardt who coined the term, describes it as a blended model, which incorporates elements of roles such as mentor, coach, consultant and critical friend, as well as strategic co-planner and pastoral carer. Ideally, the companion is a partner who ‘walks with’ rather than ‘telling how’. They companion with a principal, helping them develop the necessary personal and professional capabilities to support the learning and growth of the students and the community in their care. Because the wellbeing of the leader is recognised as important to effective leadership and a person’s wellbeing encompasses multi dimensions, professional companioning has a holistic focus on the person as a human being.

How did we implement the project?

In May 2017, all the participants undertook preparation work, which included:

- Professional reading about the research and theory of professional companioning and the underpinning key concept of ‘Learning Power’ which describes the natural learning capabilities of each human being.

- Completing an individual Empowering Leadership Learning Inventory. This provided each person with feedback about their learning profile framed around the following elements: changing and learning, critical curiosity, meaning making, creativity, learning relationships, strategic awareness and resilience.

- Developing an agreement outlining expectations and commitments.

- Information from the Regional Director, Sue Beynon, regarding system requirements and anticipated outcomes.

- Engaging with the AITSL Principal Standard and Leadership Framework currently being used by the NT Department of Education.

In June, all participants came together for a full-day of professional learning with Julianne Willis and Marilynn Willis. Over the day, participants engaged in activities that included:

- Establishing protocols using Indigenous metaphors (this resonated with many of the participants).

- Reflective thinking and discussion including, writing and drawing to explore and express what each participant wished to learn, what strengths they brought to the conversations, and what inspired them about their school.

- Focusing on the keys to empowerment by exploring where participants had previously felt empowered, the conditions that existed when they felt this way (people, resources, their role, their family story etc.) and motivators and constraints.

- Data analysis of their individual ELLI profile and the Arnhem Leader group bar graph that combined all individual data. The data was used to identify what each person was currently doing to develop themselves and others in their context and potential areas for further development.

- Principals reflecting on AITSL’s Principal Standard document to consider how much time they gave to operational, relational, strategic and systemic foci. They used this to further explore opportunities for themselves and their schools, and to refine ISMART goals they had drafted earlier.

- Developing a six month plan to grow themselves and others.

- Allocating each participant a coach and having an individual coaching session.

As the principal’s personal and school’s ISMART goals were developed, it was ensured that these were aligned to the Arnhem region’s strategic priorities to improve outcomes for students, families and communities.

From July to November 2017, each principal is carrying out planned actions to achieve their ISMART goals. Their ongoing work is supported by two formal coaching sessions a month apart, leading into final phase of the project.

The coaching conversations are very much focussed on co-constructed goals of the both individual principal and the goals set for their school. Regular reflection on progress and as well as feedback from their two coaching sessions informs further planning and refined or renewed goal setting. Principals are capturing learnings from this process in their journal.

In December 2017, all participants will come together for a final workshop to share their learning journey and outcomes, undertake group reflection, and an evaluation process to conclude their 2017 learning leadership work.

Case study 1: john sarev

John is an aspiring principal who is currently deputy principal at Nhulunbuy High School.

This role provides John an opportunity to engage in whole school leadership and support the school principal, who is also the Northern Territory Principal’s Association president. John chose to move to Nhulunbuy because he was ready for a school leadership challenge where he had an opportunity to ‘co-construct’ change with others. A key driver was to support students and staff to have bright futures, through the establishment and integration of a new Indigenous boarding school called Dawurr at Nhulunbuy High. He believes that the complexity of both the Yolngu and non-Aboriginal cultures that are part of the school, demands that he is strongly connected to community, and that he learns from others who can help him understand ‘the way we do business here’.

Having been an Assistant principal for 5 years at another school John had previously participated in the Department of Education’s leadership development program ‘Tomorrow’s School Leaders’, and used elements of coaching as part of collaborative practice in a professional learning team at the school. He is also currently completing Growth Coaching training, alongside the Companioning Coaching project. As a result, he finds himself reviewing past behaviour in the light of new theory and insights gleaned from his learning journey.

John has appreciated the opportunity to focus closely on his own practice and has questioned what it means to be an early career principal, exploring the demands of the job, recognising and becoming more aware of his accountability to different stakeholders, understanding their hierarchy, and prioritising students, in the process.

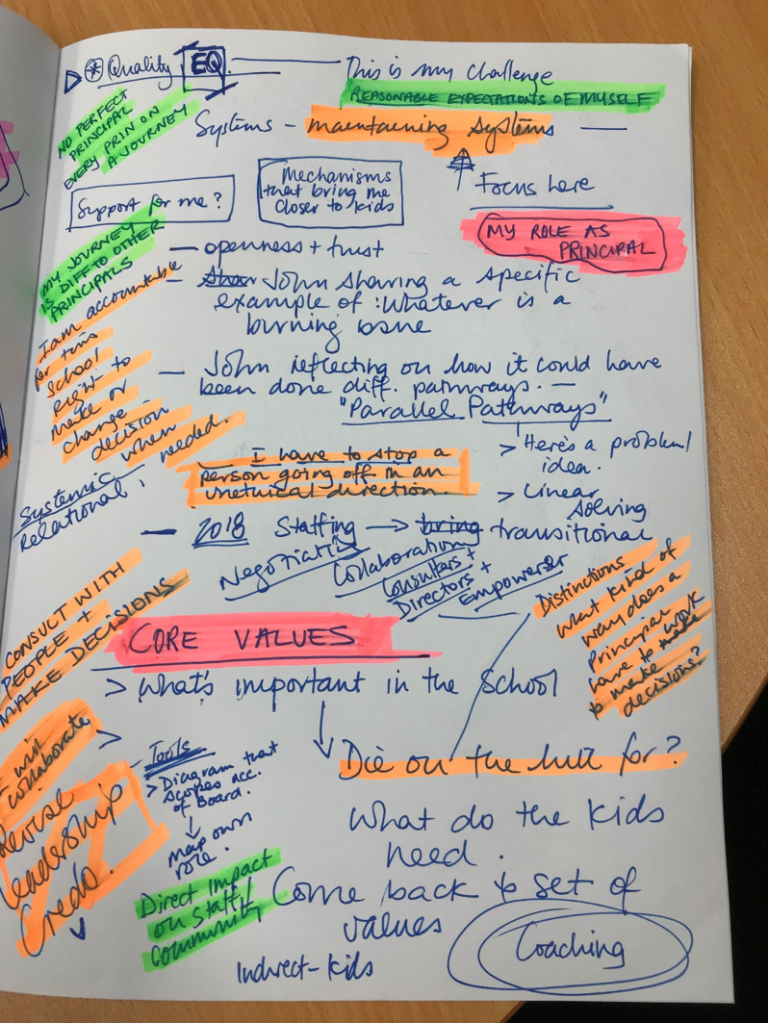

In addition to the discussions with his coach John is using a professional journal in which he has recorded information, feedback, links to resources and his own thoughts which capture reflections on his daily practice and learning experiences. In doing so, he finds he is thinking more creatively and becoming much more aware of where he works effectively and what areas are most challenging for him. His coach has helped him identify challenges and stretch in a non-threatening way.

“By asking what will I be prepared to die in a ditch for?’ I have clarified different priorities in my work and I seek to balance those with the demands of the Department” (John Sarev).

John has sometimes ‘felt like a buffer’ between the agency and the school. In his coaching sessions he explored the challenge of sharing information, asking staff to do more, and asked himself-“What will I do to safeguard the kids and staff I manage?”

John has found that the professional companioning has brought him greater role clarity and a stronger sense of the necessary strategic direction for the school. It has provided opportunity for deep thinking, access to a wide range of useful resources and organisational tools and helped him to implement the school’s teaching and learning work.

“My coach encouraged me to think outside the box, in a visioning process. I identified the characteristics of a hero, which led me to revisit old Star Trek episodes where Captain Picard had to make hard decisions in dealing with moral and ethically challenging situations with empathy and compassion. My companion conversation led me to reflect on my own leadership challenges. I could see how my previous experience and pedagogical practice as an English teacher using the narrative in popular culture and literature, can help me understand my persona as a leader” (John Sarev).

For John, the experiential learning of ‘on the job – for the job’ is highlighting the reality that at times the work of a principal can be very isolating. Through his companion conversation, his coach shared stories illustrating the ways she had managed this, which established a sense of common ground and what is ‘normal’, at the same time as highlighting that each principal’s learning journey is unique.

“I understand my core values better and what are reasonable expectations of others and myself. I am being challenged in ways I have never been before and coaching gives me permission to ask questions which always brings me back to reflect on my own behaviour. I have learned to not put myself at risk and I understand the importance of ‘me’ time, for my own wellbeing, as well as modelling this for others” (John Sarev).

John is now a part of the professional learning community of participating Arnhem principals, and through the professional companioning project he is deliberating connecting with other principals.

“Coaching has helped diminish the loneliness somewhat and has helped me believe that there is a future for me in this role” (John Sarev).

Case Study 2: Cheryl Dwyer

Cheryl has been teaching in a number of remote and very remote Arnhem communities for many years and has significant experience acting as a principal prior to becoming an executive contract principal at Numbulwar where she has been for two years. As a developing leader, Cheryl has undertaken Growth Coaching training, which she uses effectively with all staff for performance development and has some counselling training also, which has been useful in working with students, staff and families.

“Through the Companioning Project, I have felt empowered, and have developed many ideas on how to approach professional development with staff to make it more effective” (Cheryl Dwyer).

Despite her knowledge and experience, she is still facing ‘hiccups’ and finds dealing with critical situations for the first time challenging. Like John, Cheryl values the fact that her coach is very experienced in the business of school leadership and is aware of the kinds of issues that she deals with in a remote Indigenous community. She has found that it saves time by not having to provide details of her context, and more importantly, allows her professional companion to be a coach (outside the system) who provides a ‘safe’ place to talk honestly, without risk, but also knowing that the coach will ‘get it’.

Cheryl appreciated it when her coach adopted different roles within the companioning conversation, taking off the coaching hat to become a critical friend, bringing elements of mentoring into the conversation.

“My coach used Edward de Bono Six Thinking Hats to successfully guide me through an issue dealing with some inappropriate professional behaviour, which had risks for the teacher, school and the agency” (Cheryl Dwyer).

With the support of her coach, analysis of her ELLI profile and through ongoing critical reflection, Cheryl has experienced considerable personal growth and confidence, seeing herself as a professional who is able to work with others to solve problems.

“At the first workshop when the participants shared their profiles, it was nice to feel supported, sharing my profile with others and seeing where different people operate from” (Cheryl Dwyer).

Previously she felt pressure to behave in a way that she felt was almost ‘god like’, but now is allowing staff to see her own vulnerabilities and ‘be human’, without feeling like she is letting them and herself down.

“She has taught me techniques for self-management, and helped me become more aware of my own behaviour and how others experience me” (Cheryl Dwyer).

Because of her engagement in the project, Cheryl is using the process of planning, implementing and reviewing actions to achieve her ISMART goals to improve her school while also learning how to lead herself and others. In a context where funerals and other cultural activities can have quite an impact on those plans, it has been a critical skill for Cheryl to be able to adapt and manage people and processes, so that those things do not derail all their efforts. As a result, Cheryl believes she is now more creative and more resilient.